The Founder of Modern Karate Do.

|

Gichin Funakoshi (1868-1957) On the island in the sea to the south, |

|

Gichin Funakoshi - 1922 |

If there is one man who could be credited with

popularizing Karate, it is Gichin Funakoshi. Funakoshi was born in 1868 in Shuri,

then the capital city of the island of Okinawa. He started practicing Karate

while in primary school but didn't begin his mission of spreading it to the

outside world until he was 53.

Funakoshi was born into a well-to-do family of scholars in Shuri, Okinawa, in

1868. His grandfather had been a tutor for the daughters of the village

governor, and had been given a small estate and "privileged family"

status in return. Gichin's father, however, was a heavy drinker, and squandered

most of the family's wealth, so young Funakoshi grew up in a home that could

provide very few luxuries.

As a teenager, Funakoshi was sickly and weak. Fortunately, when he finally

started primary school, he happened to be in the same class as the son of

Yasutsune Azato, a renowned Karate master who had served as a military chief

for the king of the Ryukyu Islands. Azato took Funakoshi on as his only

student, teaching him late at night because of laws which forbid the teaching

or practicing of Karate.

It was from Azato and Azato's close friend Yasutsune Itosu that Funakoshi

learned most of his martial arts. From childhood until he left for Tokyo in

1921, Funakoshi studied diligently from these two masters, learning not only

shuri-te Karate, but Chinese classical literature and poetry. He also spent a

short time studying under Itosu's master, shuri-te founder Sokon Matsumura.

Funakoshi took a job as an assistant schoolteacher in 1888 at the age of 21,

and also took a wife about the same time. He supported his wife, his parents and

his grandparents on a salary of about three dollars a month. His wife, also

Karate adept, encouraged Funakoshi to continue practicing. In addition, she

took a job working in the fields during the day and then wove fabrics at night

to help make ends meet.

In 1901, Karate practice was legalized in Okinawa, and its study became

mandatory in middle schools. Securing permission from Azato and Itosu,

Funakoshi announced that he would begin formally teaching Karate. He was 33

years old.

There are many stories about Funakoshi's exploits as a youth. One thing is

certain: he found more honor in avoiding a fight than in starting one, and he

believed there was more courage in fleeing a confrontation than in defeating an

enemy. He claimed to have only used his Karate against another person one time,

during World War II. A thief tried to attack him, but Funakoshi stepped out of

the way and grabbed the man's testicles. He held the man in that position until

a constable passed by. Although Funakoshi had not started the altercation, he

later revealed that he always felt shame about that day because he had not

avoided the confrontation.

It was that "true spirit of Karate" that Funakoshi spent his entire

life trying to achieve. Mas Oyama, who later created kyoku shinkai Karate, once

trained under Funakoshi, but quit because Funakoshi's Karate was "too

slow" and seemed more like a lesson in etiquette and discipline. But this

was how Funakoshi wanted it. He taught that Karate should not be used for self

defense-even as a last resort-because once Karate was used, the conflict became

a matter of life or death, and somebody was going to get injured. Funakoshi

always remembered the proverb Soken Matsumura taught him: "When two tigers

fight, one is bound to be hurt. The other will be dead."

Funakoshi became so skillful at Karate that he was chosen to teach it to the

reigning King of Okinawa. Before Funakoshi left the island, he had already

risen to the position of chairman of Shobukai, the martial arts association of

Okinawa.

In May 1922, the Japan Education Ministry organized the first All Japan

Athletic Exhibition of Ochanomizu in Tokyo. Wanting the event to be as

comprehensive as possible, the ministry decided to include Karate. As the

province's leading practitioner, Funakoshi was the obvious choice. The Japanese

budomen, tremendously impressed by Karate, immediately set out to persuade

Funakoshi to stay and teach the dynamic martial art to Japanese youth. He

accepted the project with vigor, because he harbored a secret desire to see

Karate proliferate as kendo and judo had.

The arrival of Gichin Funakoshi was inauspicious, to say the least, and no one

seriously expected anything to come of his visit to Japan. At 51, the

mild-mannered high school teacher from Naha was already well past his prime.

But how were they to know that Gichin Funakoshi was destined to become the

Father of Japanese Karate and would set in motion the forces of a little-known

martial art which would one day sweep the world?

Funakoshi Karate was well received by the Japanese, and judo founder Jigoro

Kano asked for private lessons on basic Karate kata (forms). Funakoshi taught

Kano for several months and then arranged to return to Okinawa. Before he could

leave, however, Hoan Kosugi, a popular artist of that time, asked Funakoshi to

teach both him and his fellow artists Karate, because there was no one else in

the area who could. It was then Funakoshi realized that, if he were to spread

Karate throughout Japan, Tokyo was the place to do it.

Judo founder Jigoro Kano was so impressed with Gichin Funakoshi's Karate that

he asked for, and received, private Karate lessons from Funakoshi for several

months.

Taking up residence at a dormitory for Okinawan students at Keio University,

Funakoshi began teaching Karate in the dorm's lecture hall.

Funakoshi became a subject of some controversy only a few years after

relocating to Tokyo. For centuries, Karate had been written two different ways

in Japanese. One way used the characters for "Chinese hands," and the

other used the characters for "empty hands." Although both were

pronounced "Karate," they were written differently. Funakoshi agreed

with the obvious historical allusion in the "Chinese hands"

characters, but he felt that the use of "empty hands" not only emphasized

the art of self-defense without weapons, but also characterized the sense of

emptying one's heart and mind of earthly desires and vanity. When he wrote his

first book, Ryukyu Kempo: Karate, in 1922, he used the "empty

hands" characters exclusively.

Funakoshi is credited with standardizing the writing of Karate, a feat which,

though angering several martial arts masters at the time, met with eventual

universal approval.

In 1923, a massive earthquake shook Japan, and Tokyo was razed in the ensuing fire.

Although the dormitory Funakoshi called home and still taught out of was

spared, many of his students died or disappeared. For a short time he suspended

his instruction and spent the next several months assisting in the massive

cleanup.

Funakoshi's next major task was the creation of an all-new dojo (training

hall). Because he had a difficult time raising funds, the building was not

started until 1935. A year later, the world's first freestanding Karate dojo

was completed. Funakoshi named the school "shotokan" (the house of

Shoto) after the pen name he used when writing poetry. When he stepped through

the doors for the first time, he was almost 70 years old.

As he became increasingly busy with his dojo, Funakoshi began handing over his

teaching assignments at the various universities to his students. He still

conducted demonstrations, however, including regular performances before

Emperor Hirohito, who invited him to the Imperial Palace on an annual

basis.

The United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, and times grew

hard in Japan. Funakoshi's third son, Gigo, who was supposed to inherit his

father's school, died of tuberculosis in 1945. A few months later, Funakoshi's

dojo was destroyed by Allied bombers. In that same year, the battle for Okinawa

began in earnest, and many people fled to the island of Kyushu, including

Funakoshi's wife, who had remained in Shuri during his residence in Tokyo. The

couple were reunited at a refugee camp on Kyushu, and Funakoshi stayed with his

wife until her death in 1947. He then boarded a train for Tokyo to start all

over again.

More than just the buildings had been demolished in Japan during the war;

national spirit had been eroded as well. The occupying forces disallowed

martial arts instruction. Fortunately, because of Funakoshi's association with

the Ministry of Education, Karate was classified as physical education, not a

martial art. He therefore began teaching again, and within a few years was

drawing martial artists from other disciplines, all of whom were longing for a

place to practice. Included among these new recruits were American servicemen,

who were amazed at this form of exercise. For every GI who returned to the

United States with a Karate tale, Funakoshi received two more letters from Americans

who wished to become students.

Funakoshi, approaching his mid-80s, found a new task. He had spread Karate

throughout Japan, now it was time to spread it throughout the world. In 1953,

after several requests from Americans for qualified Karate instructors, he

began sending some of his finest students to the United States to begin

teaching martial arts. These men, who included Masatoshi Nakayama, Hidetaka

Nishiyama and Tsutomu Ohshima, were America's Karate pioneers. Funakoshi

eventually organized his students and their schools into the Japan Karate

Association in 1955, one of the first international martial arts associations.

Two years later, at age 89, Funakoshi died in his sleep, leaving behind a

legacy so huge that its shadow stretched from the shores of tiny Okinawa across

the Pacific Ocean to the United States. Funakoshi took little credit for

Karate's immense popularity, but few denied that he had almost single-handedly

brought the art to Japan and subsequently sent it overseas.

|

|

|

|

|

Funakoshi's Teachings |

Funakoshi concentrated almost entirely on teaching kata.

He brought 15 kata compiled from various styles, and developed some himself.

Although he taught a little kumite, his approach to Karate was based on the

following precept: "Once you have completely mastered kata, then you can

adapt it to kumite." The closest thing to Karate in Japan when Funakoshi

arrived was the atemi (technique of striking the vital parts of the

body).

Funakoshi also stressed the importance of toughening each part of the body

until it was as hard as iron. He constantly beat himself with an oak staff to

drive home his point to his students! A makiwara (straw-padded pole) was used

to toughen the hands and feet.

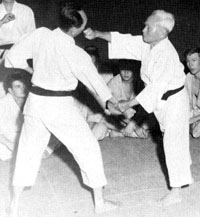

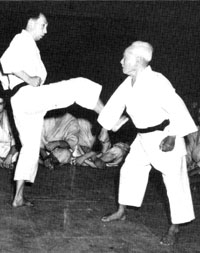

Even in his 50s and 60s Funakoshi was agile and

unusually strong, especially in defense. Funakoshi's defense was very difficult

to penetrate during training, no matter how hard his students tried.

Perhaps the most important work Funakoshi accomplished was during the 30's when

he systematized Karate kata and techniques, incorporating a code of ethics and

discipline found in the other Japanese martial arts. This codification forged

the bonds that would one day transform Karate into a mental and physical

discipline which would rival judo in "finding the way." He published

three books on the subject-the second and the most important one of which, Karate-Do

Instructions, was published in 1939. Aided by his son Yoshitaka, Funakoshi

continued teaching Karate throughout the rest of the decade at the Mejiro dojo as

well as at the college clubs he had organized. When the war broke out, the

number of students gradually decreased because of the draft.

Most of Funakoshi's former students remember him as a mild, gentle and friendly

person. The Okinawan master always shook hands and put his arm around them when

they met. He wasn't bossy, but when he was teaching Karate, he was very

strict.

He didn't drink, smoke, gamble or play around with women. He was the kind of

man who never made enemies. Outside of Karate, his two main interests were

calligraphy and composing Chinese poems. He was convinced that living a good,

clean life created a character best suited for the study of Karate. He educated

his students by trying to get them to fulfil their own potential.

Before he brought Karate to Japan from Okinawa, it was just a local system in

Okinawa. Upon bringing Karate to Japan and seeing Japan's traditional martial

arts, such as judo and kendo, Master Funakoshi patterned Karate after these

arts to a large degree and made Karate popular. He had the technical and

philosophical ability to do this and got people to accept his ideas about

Karate rather easily. This was one of his biggest contributions to the martial

arts. That's why it is often said that Master Funakoshi was a great philosopher

and a great technician. On Karate's spiritual side, too many people look on the

surface of Karate and only see violent techniques: kicking, punching and

striking. They see Karate as something that's only very dangerous. But Master

Funakoshi combined Karate techniques with traditional budo (the martial way) to

put the essence of budo into Karate-a real way of the martial arts. That's why

Master Funakoshi's students did not have any violent ideas. He taught that

Karate is defensive, never offensive. When Master Funakoshi studied in Okinawa,

you couldn't publicly practice Karate. It wasn't for everybody and was secret.

Karate practitioners were like a secret society. But Master Funakoshi opened

Karate to the public and proved that its techniques are effective. And yet,

Master Funakoshi not only stressed the technical aspects of Karate, he

emphasized that Karate has a philosophical background. To him, Karate had a

philosophical essence that carried over into other parts of students' lives. In

other words, Karate was a way of life: Karate-do. Otherwise, you only have

Karate-jutsu, which is just the art of fighting. Master Funakoshi made this

distinction.

|

|

When you first met him, he looked very old. Nobody would guess that he was a

real grandmaster. That's how humble he was. He always felt he needed more

study, and was a great example of a genuine martial artist. Some masters, once

they reach a certain point, like to show off. "I'm a fifth-degree black

belt; I'm the strongest man in the world," they spout. Such behavior had

nothing to do with Master Funakoshi's philosophy. He felt no need to show off.

Once he put on a gi (Karate uniform), however, and went into the dojo, he was

different- right away. He still didn't show off, but he changed. When he stood

in the dojo, he looked as though one of his movements could destroy anything.

That's how good his techniques were. Then, when he finished training, he again

became very humble. Master Funakoshi always said that the martial artist's

etiquette was very important, and that etiquette was the sign of the true

martial artist. That's why Master Funakoshi didn't look like a so-called

"real" grand- master. He didn't show that kind of thing except in the

dojo.

Master Funakoshi was very wise and had a broad mind. He felt that Karate should

be open to everybody; he wanted everybody to know the art. If you have some

nice medicine, he felt you should share it with everybody. That's why he agreed

to form an association, and that's why he created the JKA. He never said

anything about any one particular style. For instance, some had goju style,

while others had wado style. But he never taught the need for styles.

Funakoshi always believed kata was the secret to becoming skilled in Karate. He

made students practice the pinan and naihanchi forms for at least three years

before he allowed them to progress to the more advanced kata. The repetitious

training paid off, though, because his students developed the most precise,

exact Karate taught anywhere.

Funakoshi was a man of Tao. He placed no emphasis

on competitions, record breaking or championships. Instead, he emphasized

self-perfection. He believed in the common decency and respect that one human

being owed another. He was the master of masters.

|

Some final words

|

As Karate legends go, Gichin Funakoshi's life was not terribly exciting. He

never challenged anyone to a sword duel, never attempted to dismantle a bull's

horn, never had a presumptuous nickname and, in fact, never left the islands of

Japan. He was a poet, and a schoolteacher, and the closest he ever came to

seeing battle was when he mediated a dispute between two neighboring

villages.

Yet Funakoshi is one of the most honored, cherished and memorable martial

artists in history. His innovations left indelible marks on the art form we

know today as Karate. Not only was shotokan Karate, the style he founded,

influenced by Funakoshi, but dozens of other styles as well.

Funakoshi died in 1957 at the age of 88, after humbly making a tremendous

contribution to the art of Karate.

From http://www.fightingmaster.com/masters/funakoshi/index.htm